In today's newspaper Karen MacPherson handicaps the children's books nominated for the three top awards given by the American Library Association. It's been a while since I read a good picture book. When I went back to college my friend Trudy would often invite me to dinner. After dinner and cleaning up it was time for her (then) young daughter's bedtime. The ritual included reading a bedtime story. In the long list of debts I can never repay, those meals and those stories remain precious to me. If I learned how good picture books can be, it's not a literary genre I keep up on.

Among MacPherson's contenters, although not one of the favored picks, is The Old African. MacPherson mentions the illustrator, Jerry Pinkney for the Caldecott Medal. The book's author, Julius Lester is mentioned as a contender for the Newbery Medal for his book Day of Tears. I haven't read Lester's first book (1969), but it has one of my all-time favorite titles: Look Out, Whitey! Black Power's Gon'Get Your Mama! Pinkney and Lester have collaborated on other books before, and both men have produced an exceptional number of books. Outside the miniscule number of mega-hits, children's book publishing is only marginally lucrative for authors and illustrators. There would be few writers if not for the love of books. No where is the love of books more evident than among children's authors and illustrators.

I was curious to learn more about The Old African. The snippet from The School Library Review on the Amazon page begins:

As the story opens, the Old African is watching a boy being whipped on a plantation in Georgia. He is putting a picture into the minds of his comrades–a picture of water as soft and cool as a lullaby–and the picture stops the boy's pain.I wondered whether this is appropriate for children. Lots of children's stories are far darker than we remember. At least on some level of remembering; there is a part of my belly that churns when I even think of the witch in Hansel and Gretel. I'm not one for believing in scaring children, but I also know that childhood is a time of facing fears; those brave children.

Many years ago I gave a nephew a picture book, Pink and Say written and illustrated by Patricia Polacco. At Carol Hurst wonderful Web site about children's literature the summary of the book follows:

This heart-wrenching historical picture book, based on a true story, presents us with two men from the Union army who meet after a battle of the Civil War. Say, the white younger man, has been wounded. Pink, a black man, carries him home to where his mother is surviving in ruins of a deserted plantation. Pink is determined to rejoin his unit in spite of mother's protest. Say, who was deserting when wounded, only agrees because of the danger they present to Pinks mother. Marauders come and kill her while they hide in the cellar. On the way to the front lines they are captured by confederates and taken to Andersonville prison, Pink is hung. Say survives to become author's great-great grandfather."Heart-wrenching" indeed, I can never read that book aloud without choking back tears at the final page. It's odd in away for me to think that I mustn't cry over a book in front of children. Part of that is wanting children to be unconstrained in forming their own reactions to books.

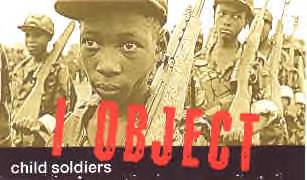

One reviewer at Amazon thinks that children shouldn't be exposed to Pink and Say. Because I at least momentarily had a similar reaction to The Old African I cannot dismiss his reaction out of hand. Child soldiers are a part of our history too. "I OBJECT!" Never should children be soldiers. While it's right to do everything possible to sheild children from that fate, it's unfair to kids to pretend war never affects children. My sister told me that her first reaction to my gift of Pink and Say to her young son was: "What is this?" but she thanked me because the book was special to her son. It even prompted a Halloween costume.

War, what a subject. By way of James Walcott I first heard of James Hillman's A Terrible Love of War. Hillman, a Jungian psychologists suggests our love of war is mythic. Chris Hedges's book, War is a Force that Gives Us Meaning describes from his years as a war correspondent how this love of war can overtake us.

Reading more African and Afro-friendly blogs lately, sometimes I've felt overwhelmed by the stories of suffering. It's little wonder people tend to tune the news out. For the Martin Luther King Holiday, Maria Luisa Tucker wrote a piece, Finding Words to Talk About Race. She wrote:

Conversations about race and ethnicity are conversations about sex, hate, love, ignorance, history, guilt, shame and anger. It's embarrassing, uncomfortable and emotionally draining.We should try to talk about difficult and important subjects. War stories are important because we cannot contextualize war by reason alone. Stories provide a context where our emotions play a critical role in our understanding.

Given the choice, we'd rather not talk about it. But given the state of things, we should try.

In the mid-sixties Julius Lester worked with the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, SNCC pronouced "snick." I doubt that he set out to become a well-known children's author. (I should hasten to add that Lester has written both book of adult non-fiction and fiction as well--the fellow is prolific.) But Lester's storytelling isn't so surprizing given the hard subjects he's tackled. Books are very important, even in this Digital Age. Children's literature provides a vocabulary from which children can develop a language to speak about the world and the possibility for building a better one.

No comments:

Post a Comment